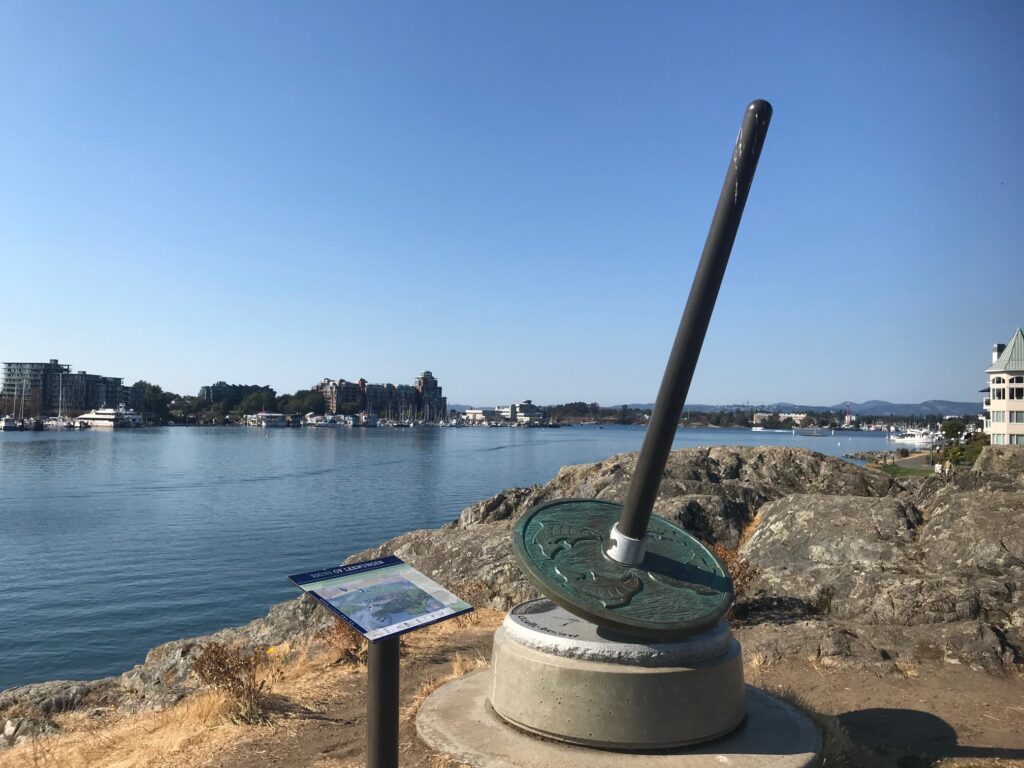

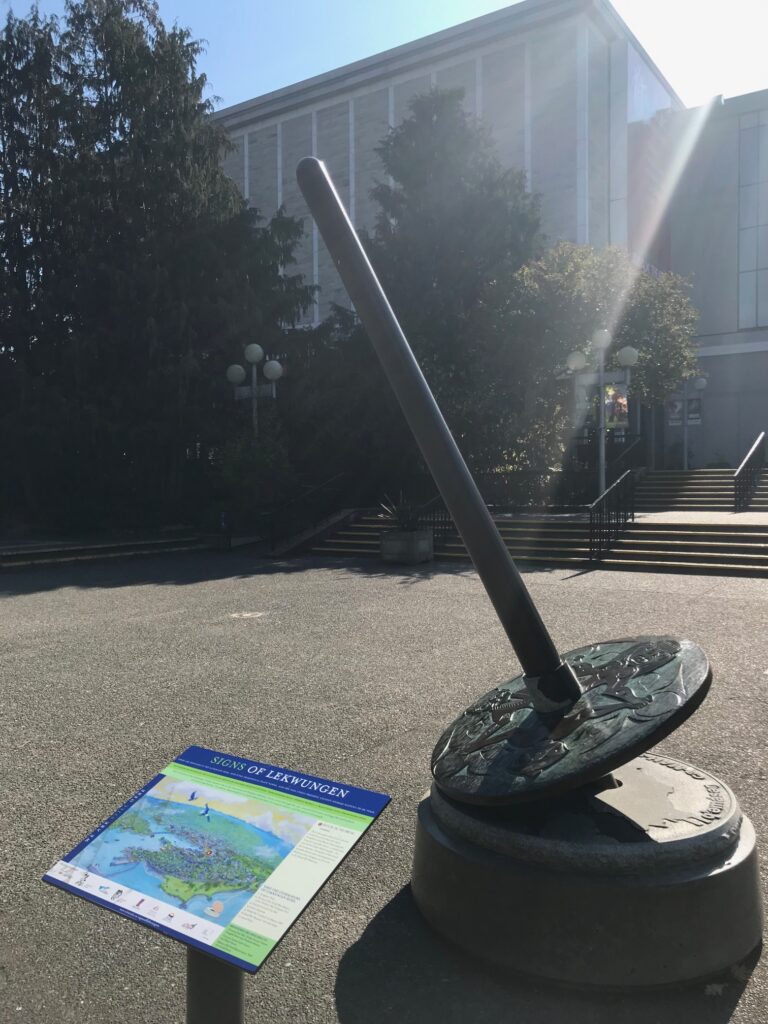

I think that a key component of environmental education is nurturing a sense of place. In order to learn about environmental systems and approach environmental challenges, we must also understand our place within the web of the wider world. Cultivating this foundational sense of place involves learning more about the land you are on. As a settler living on unceded Lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwungen) territories, learning about the land is inextricably tied to learning more about the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples. In 2008, the Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations and the City of Victoria collaborated on the The Signs of lək̓ʷəŋən, a series of seven spindle whorl (tool used to spin wool) statues marking places of particular cultural significance to the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples around the inner harbour of the city. The development of the city actively obscures the ways in which the Lək̓ʷəŋən have interacted and continue to interact with this land. This installation serves to make visible the culture of the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples and educate people about the cultural significance of this area, something that gets hidden behind colonial infrastructure.

Although I have visited some of these site markers before and knew a bit about them, there are some I’ve never been to and I’ve never visited them all in one go, so this seemed like a good starting place for my backyard adventure project. Now to decide how to do it. Cycling seemed a bit too fast for this endeavor. I wanted to have time between sites to reflect on the land I was moving over and on how colonialism has shaped the reality I see today. So instead, I decided to run. In total, the run was 12km and I managed to see six of the seven spindle whorls. It’s quite moving how different the land is now than what is described on some of the signs. For example, outside city hall, skwc’әnjíłc (skwu-tsu-KNEE-lth-ch), the area is described as having been full of “willow-lined berry-rich creeks and meadows [meandering] down to the ocean.” What was once a rich ecosystem has now been paved over. Having now learned a little bit more, I think I will think of these places differently every time I visit them. I am really grateful to have had the opportunity to learn a bit about the cultural significance of each of these places to the Lək̓ʷəŋən and also to learn a couple more Lək̓ʷəŋən place names. I intend to continue this learning in future components of this project and beyond this project in my own personal and professional life.

Unfortunately, after running in circles for 20 minutes or so, I concluded that one of the site markers must have been removed as part of a soil remediation project at Laurel Point (Lək̓ʷəŋən name not known). This in itself was interesting to learn about and reflect on. The area around Laurel Point was a burial ground for the lək̓ʷəŋən until 1850. A short while later, it housed a paint factory and the land was infilled with hazardous materials (hence the soil remediation project). The work to remediate this site is ongoing, and the city hopes to use this project as an opportunity to meaningfully engage with the Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations about what they would like to see done with the land. With this history and the ongoing efforts to remediate the site and repair relations, this place is not only interesting to learn about, but I think that it could be a great case study to talk about in a future classroom. From colonial dispossession and environmental contamination, to Lək̓ʷəŋən culture and reconciliation, this place is full of learning opportunities.

How could this be applied in the classroom?

- Single Site Case Study – As was discussed above, the location at Laurel Point has a really interesting history that could be tied into multiple topics relevant to the B.C. curriculum. This could be a really great case study to investigate as a class and learn more about the cultural significance of the place to the Lək̓ʷəŋən, the historical and ongoing impacts of colonialism, dispossession of land, environmental contamination and remediation, and ongoing processes of reconciliation.

- A Tour of the Signs of lək̓ʷəŋən – Like my running tour, you could do a similar tour with a class. The entire route is easily bike-able, so it could make a good cycling tour, but obtaining bikes and taking kids on the road with them may be difficult to pull off. The distances between the site markers may be too far for a walking tour, especially if you have limited amounts of time. If it’s possible, you could break the class into groups and have each group study one of the sites and present back to the class.

- Uncovering Place Project – During my undergrad I took several Indigenous Studies classes. In one such class, we undertook a project called Uncovering Place, where in groups, we identified a location within W̱SÁNEĆ territories, learned it’s SENĆOŦEN name, and learned about its cultural significance to the W̱SÁNEĆ people. At the end of the project, each group presented the place they studied to the class. I think you could do this same project in a high school social studies class relating to whatever territories you are working on.

- Colonial Reality Tour – I’m not sure if these tours are still running after COVID, but before COVID, Cheryl Bryce (Lək̓ʷəŋən) ran tours around the city stopping at sites with significance to the Lək̓ʷəŋən and teaching people about each site. This could be a great field trip for a class.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.